Ways of Living

Stocking and preserving food grains was an annual family ritual in most families when I was a child. All the furniture in one room would be pushed back against the walls to make room in the middle. Jute sacks (kattas) filled with wheat or rice would be brought in. The cotton thread that sealed the sacks would be carefully pulled off and the contents emptied on the floor in a big heap. All the grain would be sifted to remove the chaff and then all of us would sit around the heap of sifted grain with our steel or brass plates placed upside down on the floor right next to the heap of grain. With a flick of the right hand, one would scatter some grain onto the plate and pick out the stones, chaff or other impurities and then slide the clean grain off the plate on one’s left. The cleaned grain was then given a good rubbing of castor oil and stored in tin drums. The grain stored at the bottom of the drum was rubbed with very little castor oil while the grain at the top received a more generous coating. Gravity ensured that the castor oil from the grain at the top would eventually coat the grain at the bottom. Without this carefully calibrated and judicious use of the preservative (castor oil), the grain at the bottom of the drum would be soaked in excess castor oil and would turn bitter, rancid and inedible by the end of the year. Split cereals got the same treatment, too. Other pulses, cereals and ground spices were stored in air-tight glass jars and barnis with a few sea-salt crystals and pieces of dry dung cakes! The salt crystals soaked in the moisture and kept the ingredients dry while dung cakes actively discouraged pests and insects!

Stocking and preserving food grains was an annual family ritual in most families when I was a child. All the furniture in one room would be pushed back against the walls to make room in the middle. Jute sacks (kattas) filled with wheat or rice would be brought in. The cotton thread that sealed the sacks would be carefully pulled off and the contents emptied on the floor in a big heap. All the grain would be sifted to remove the chaff and then all of us would sit around the heap of sifted grain with our steel or brass plates placed upside down on the floor right next to the heap of grain. With a flick of the right hand, one would scatter some grain onto the plate and pick out the stones, chaff or other impurities and then slide the clean grain off the plate on one’s left. The cleaned grain was then given a good rubbing of castor oil and stored in tin drums. The grain stored at the bottom of the drum was rubbed with very little castor oil while the grain at the top received a more generous coating. Gravity ensured that the castor oil from the grain at the top would eventually coat the grain at the bottom. Without this carefully calibrated and judicious use of the preservative (castor oil), the grain at the bottom of the drum would be soaked in excess castor oil and would turn bitter, rancid and inedible by the end of the year. Split cereals got the same treatment, too. Other pulses, cereals and ground spices were stored in air-tight glass jars and barnis with a few sea-salt crystals and pieces of dry dung cakes! The salt crystals soaked in the moisture and kept the ingredients dry while dung cakes actively discouraged pests and insects!

Preservation of chillies was a carefully orchestrated and planned affair. The calyx and the stem were plucked off, the chilli was broken into two and the dry seeds were removed before grinding the rest. Varieties of chillies were processed and then mixed in certain proportions to get the desired colour, taste and texture. All this required lot more precaution and was usually done outside the home.

And when large stocks had to be preserved (for large families), outside help was often sought and helping hands were hired. Women, usually rabaari women, would arrive with their big mortars and wooden pestles to grind the spices and pick clean the grains. They would spread out the grains on old bedsheets, arrange themselves around the mounds of grains and start the work. The green dotted tattooed patterns on their arms seemed to dance gracefully as they settled in a synchronous rhythm while the clinking of their glass and ivory bangles and arm bands provided the background score. And ever so occasionally they would sing along to this music. Some cash and a portion of the grain was their remuneration.

With help, all the cleaning and storage of grains, spices, cereals and pulses took 3-4 days. We knew the farmers and merchants we bought the grains and food from. And we bought grains and food from the same farmers and merchants for generations. There was a sense of community and bonding in the transaction. There was beauty, practicality and care in the cleaning and storage. There was nutrition in the food, and it was preserved in natural, healthy, practical and inexpensive ways. Working women took a few days’ leave from work or sought help of friendly neighbours. The women brought cooked food and worked the afternoon away, exchanging news, stories and domestic tales, seeking and providing comfort to one another.

The entire process was environment-friendly and sustainable. The jute bags the grain was brought in were sold back to the merchants or repurposed in a variety of ways. In those days, sparrows and other birds nested in and around our homes. These houseguests too got their share of the crop. The broken grain from the all the sifting, sorting and picking was saved to feed the birds. It was fondly called chakki-charan (sparrow food). Even the cotton string the bags were sealed with was plucked off carefully and reused to pack other items or left out for the birds to build their nests with. The chaff was used to fertilize the soil. Nothing was wasted. Every fortnight wheat, millets and other grains would be taken to the local flour mill and for a small sum you could get them ground into flour in as grainy or smooth a texture and consistency as you preferred. All customised as the recipe or personal preferences called for! And then compact flourmills became available for domestic use. Almost every household acquired one and now grain could be ground fresh when needed.

But that was then. Things are different now, mostly. I still stock and store grains, pulses, cereals and spices to last me a whole year. March-April is usually the time when I wash and scour my spice barnis, the tin drums and the glass jars before the new crop arrives. This fastidious, diligent and meticulous exercise is often met with quizzical expressions from friends and colleagues who readily point out that all grocery can be bought year-round, in fact, can be had delivered at one’s doorstep. Others ridicule the Gujarati in me and assume that stocking up on grains, spices and pulses is just a Gujarati’s way of saving on a few rupees (the assumption being that all Gujaratis are cost-conscious. Gujaratis are actually value-conscious, but will talk about this some other time, maybe, and no, stocking grains doesn’t save any money either.)

Gujarat has always been a drought-prone region. Hence, stocking up on dry food grains has always been a part of the Gujarati culture. The arid and dry climate makes storage and preservation of food grains relatively easier than say, in more humid regions. Pickling seasonal fruits and vegetables to enjoy them throughout the year and building on a repertoire of skills and methods to preserve food grains without using chemicals or artificial preservatives was traditional household knowledge that was passed down every generation. Supermarkets and Hypermarkets and their promise of hassel-free year-round delivery has now made these traditions irrelevant. We have smaller homes now and the abundant supply of food obviates the need to stock, store and preserve. It’s an easy barter; it makes life convenient and stress-free. But what have we lost in the process?

We now value food by the price we have paid for it, not by the effort, knowledge, care, skill and time that has been spent on producing it. We don’t know how food is processed before it arrives on our tables. We consume artificial flavours, preservatives, food colours and additives in almost every meal. Our children cannot tell mung daal from urad daal (but can easily tell penne from fusilli) or name the types of chillies or rice and wheat varieties. Producers and manufacturers brand their products with health and nutrition promising labels such as ‘wood-pressed’, ‘cold-pressed’, ‘organic’, ‘natural’, ‘farm fresh’ and what not, over pack their products in layers of fancy plastics to ensure freshness and purity and aggressively market them (with the end consumer bearing the cost of advertising) on national television channels and online platforms. We find picking pre-packaged foods and grains in plastics off the shelf far more convenient and even desirable. Afterall, that is what the west does! The effort that goes into storing and preserving food is now termed as ‘labour’ and looked down upon. In Gujarati, the term used to denote all such work is self-explanatory of the attitude and prejudice we all harbour against such work in general and people who do such work in particular – gaddhavaitra (donkey-work). We would rather spend this time watching mind-numbing TV programmes or surfing the internet on our phones! The local varieties of grains, millets and vegetables are slowly losing this battle against plastic-packed national brands and genetically modified seeds seem to have taken over. Inherited by generations and reusable tin, glass and pottery containers used to store food are now replaced with plastic jars and containers. Jute sacks are now replaced with woven plastic bags. Birds have long disappeared from most cities and sparrows are almost on the verge of extinction. All this plastic is now polluting the air, land and water around us. Marine life is bearing the brunt of human indolence.

The long-term repercussions of this exchange are now becoming more and more visible. Health has become a serious concern. Food allergies are now common. A variety of diet fads are needed to battle these allergies, each of these diet systems offering humongous health benefits. And yet, we are not as healthy as our grandparents, nor as active! Yes, we have only now realised the need to revert to organically grown foods and concentrated efforts are now being aimed to revive local food grains and millets through seed banks. But these practices are still not sustainable. Better mills have simplified food processing and threshing, winnowing and sifting requires less manual labour. Automated plants can manufacture tonnes of pre-packaged ready-to-cook or ready-to-eat food in a matter of hours. But it still consumes a lot of fuel and energy. In US, the food industry alone is the fifth-largest consumer of fuel and energy. And even organic food and grains are packed in plastic packets to extend shelf-life and offer the convenience of being picked-off a supermarket shelf. All this plastic is still piling up! Even this organic movement we seem to have going is not sustainable.

And it’s not just about the food industry. We can see the same trend in practically every other industry or natural resource that is exploited. We are no longer satisfied with a few possessions. Since the only effort we need to invest in acquiring a new item is to surf on our phone and click a few buttons, the line between need and want has blurred; we now need a new wardrobe, new accessories and even new devices and gadgets every season. And what do we do with the old unfashionable items? Of course, we dispose them off. Or give them away to charities. And where do these disposed items go? In our land and the oceans. And do we care? Of course not! And why would we, as long as we have the convenience of picking new items off the shelves! The amount of spandex/elastane, synthetic fibres and other fashion waste that are found in landfills and oceans is perhaps next only to plastics.

From a civilisation that took pride in hard work and acknowledged the dignity of labour, we now shy away from even the most basic household chores and invent electronics to do that for us (and these electronics end up in landfills as well). Household chores have acquired a derogatory nuance and gymming gets the most favourable nod. Everything we use or consume has a price tag and its value is reduced to a number. We see the products aesthetically displayed in flashy, beautifully decorated stores and don’t know anything about how these products come about to be, or anything about the people who are engaged, employed and very often exploited (world over) in producing them.

Ways of living have changed and always change, but our current way of living is unsustainable. It is time we unlearn our ways and take a fresh look at traditional and more sustainable ways of living. It is time we learnt from our ancestors again. And we must involve our children in this exercise, too.

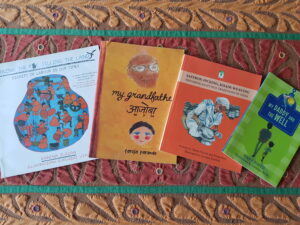

Here are some books to introduce children to some traditional ways. I hope their engagement with these traditional ways doesn’t stop at just books.

- My Grandfather Ajoba, Taruja Parande

- My Daddy and the Well, Jerry Pinto, Illustrated by Lavanya Naidu

- Saffron-picking, Khadi-weaving: Exploring Eight Eco-traditions of India, Sheela Preuitt and Praba Ram, Illustrated by Lavanya Karthik

- Turning the Pot, Tilling the Land: Dignity of Labour in Our Times, Kancha Ilaiah, Illustrated by Durgabai Vyam